Hi friends—

Like all of you, I too have been cocooned at home, reading, TikTok-ing, and eating more than I should be, frantically refreshing the news in anticipation of some imagined story where things suddenly all make sense. So far my hopes have been left unanswered.

So in this state of lockdown I thought I might do some sense-making of my own: to look past the news cycle and wonder what larger insight we might find from this experience. What can we learn from this unprecedented moment of lived history?

In 2004, a Canadian professor named Ronald Wright published a book called A Short History of Progress based on the Massey Lectures he delivered that year. In it he provides an anthropological history of humankind told through the recurring metaphor of one of its oldest stories: the deluge.

The flood myth—where a corrupt and decadent society is destroyed by a spiteful act of their god(s)—is one of the oldest, and most common, stories in our collective human memory. Versions of it exist in Persian, Judeo-Christian, Mesopotamian, and Aboriginal cosmologies. Its message (at least on the surface) is simple enough: clean up your act or face the wrath of god.

But in Wright’s telling, this story is more than a metaphor—it’s a living memory rooted in the human ecological record. Starting with the story of Easter Island and moving forward to Sumeria, Rome and the Mayan city of Copan, Wright tells us a tale about what happens when societies become too big to fail and too preoccupied with wealth accumulation and technocratic management to worry about the potential consequences of their ecological impact. In his account, these are called “progress traps”: social and technological advances that work so well that they lead to the demise of the society that creates them.

Throughout this history, Wright describes the recurring pattern that human societies have moved through on their way to collapse: reaching the carry capacity of the lands they inhabit, making poor choices on how to manage their resources, and entering into a period of socio-political disarray that leads, inevitably, into collapse. Deluge.

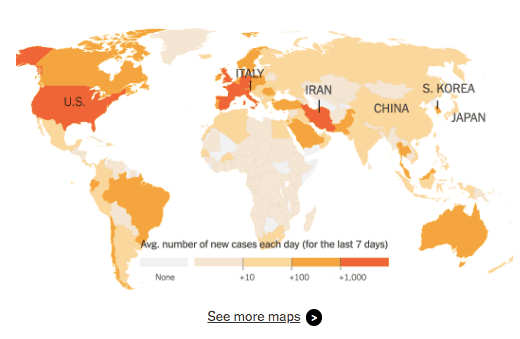

Under the current circumstances, with COVID-19 making its way across the globe, I think the metaphor is fitting; not so much as a direct analogy for what’s happening, but as a symbol of the global impact that issues have in an international political economy. There is simply nowhere else to hide.

Whereas in the past, crises have often been localized and the impacts of ecological degradation have been concentrated to particular parts of the world, in a globalized system we no longer have this luxury. Deluge has gone global.

Since we began talking about globalization as a society we’ve known this to be true, but it often takes specific instances of change for us to reflect on it. During the 2008 financial crisis this became apparent. It revealed in shocking clarity how the housing market in one country could easily destroy pensions in far-off countries: Ireland, Iceland, Greece.

Coronavirus—as an abstract, impersonal, somewhat cosmic enemy—is the first example since that time of how issues travel across the globe, not discriminating based on race, country, wealth. It’s our first truly global crisis of the digital era. It indicates how fragile our systems are, and how ill-prepared we are to deal with large-scale infrastructural challenges. For years, experts have been warning leaders about an impending ‘superbug’ crisis, and our response has been unsurprisingly shortsighted: cut budgets, wait until it’s here, and then react.

What the Coronavirus distracts us from is the even larger-scale, even more destructive enemy of climate change and ecological collapse that has been staring us down for the last thirty years or more. Sure, the clouds of smog have cleared up while we’ve all been inside, but that should only be a sign of the daily toll of the carbon economy.

Throughout the next decade and beyond, we are going to be faced with issues that challenge our basic models of how we live and eat and work. Whether its climate migration or food production or digital citizenship, the interdependencies of our lives on this planet are becoming more apparent, and our responses to these issues more urgent. We will need new systems for global collaboration and issue response.

At its best, the Coronavirus should be seen as an early indicator of the type of collaboration and data-sharing that we should strive to develop in the coming years, and a reminder of the hyper-connected world we live in. Some of the resource-sharing and modelling techniques that have been used during this time have been incredibly impressive, and hint at the type of knowledge-sharing that will prove essential as we work on responding to future global crises.

Mythologies of progress are not very fashionable these days, and perhaps with good reason—but a light dose of techno-optimism can go a long way. For all its flaws, technology has played an important role in responding to this issue, to flattening the curve, to transnational cooperation. Taking some time to reflect on what’s important, what’s at stake, and how interconnected we are has been valuable for me, and I think it has been for a lot of other people too. It just might be the awareness we need to gracefully heed the road ahead.

Stay healthy and stay inside.

Sam