I’ve been thinking about feedback lately—how we use information to inform our actions and shape our decisions. Feedback, and the way we apply it, is especially important when it comes to personal growth. Which got me thinking about flywheels. No, not the indoor cycling studio.

What’s a Flywheel?

The flywheel is a manufacturing metaphor that comes from the book Good to Great, published in 2001 by author Jim Collins. After studying hundreds of organizations, Collins developed a theory about what differentiates the good businesses from great ones. And the flywheel is a core part of that theory.

Since it was published, this book has been celebrated by business people all over the world, used as a signpost for spotting strong organizations and leaders. The flywheel is up there with “anti-fragility” as one of Twitter’s favorite mental models. To quote Collins:

Picture a huge, heavy flywheel—a massive metal disk mounted horizontally on an axle, about 30 feet in diameter, 2 feet thick, and weighing about 5,000 pounds. Now imagine that your task is to get the flywheel rotating on the axle as fast and long as possible. Pushing with great effort, you get the flywheel to inch forward, moving almost imperceptibly at first. You keep pushing and, after two or three hours of persistent effort, you get the flywheel to complete one entire turn. You keep pushing, and the flywheel begins to move a bit faster, and with continued great effort, you move it around a second rotation. You keep pushing in a consistent direction. Three turns ... four ... five ... six ... the flywheel builds up speed ... seven ... eight ... you keep pushing ... nine ... ten ... it builds momentum ... eleven ... twelve ... moving faster with each turn ... twenty ... thirty ... fifty ... a hundred.

Then, at some point—breakthrough!

The idea is simple: growth isn’t a linear process. It’s cumulative and compounding. Moving the wheel at the beginning takes a lot of effort and discipline because it’s heavy. But as things build on each other, and your team learns to convert wins from one area to others, the system itself picks up energy and spinning the wheel becomes easier. Each component of the value chain contributes to the next one. Lower pricing leads to a better customer experience, which leads to higher traffic and more qualified sellers. With each spin of the wheel, the overall product gets better and better over time. And this is how the company goes from good to great.

But enough about business.

Life on the Flywheel

While business frameworks tend to be useful for, uh, businesses, they can be reductive when they’re applied to humans. We’re not machines, after all. But they can also be really useful.

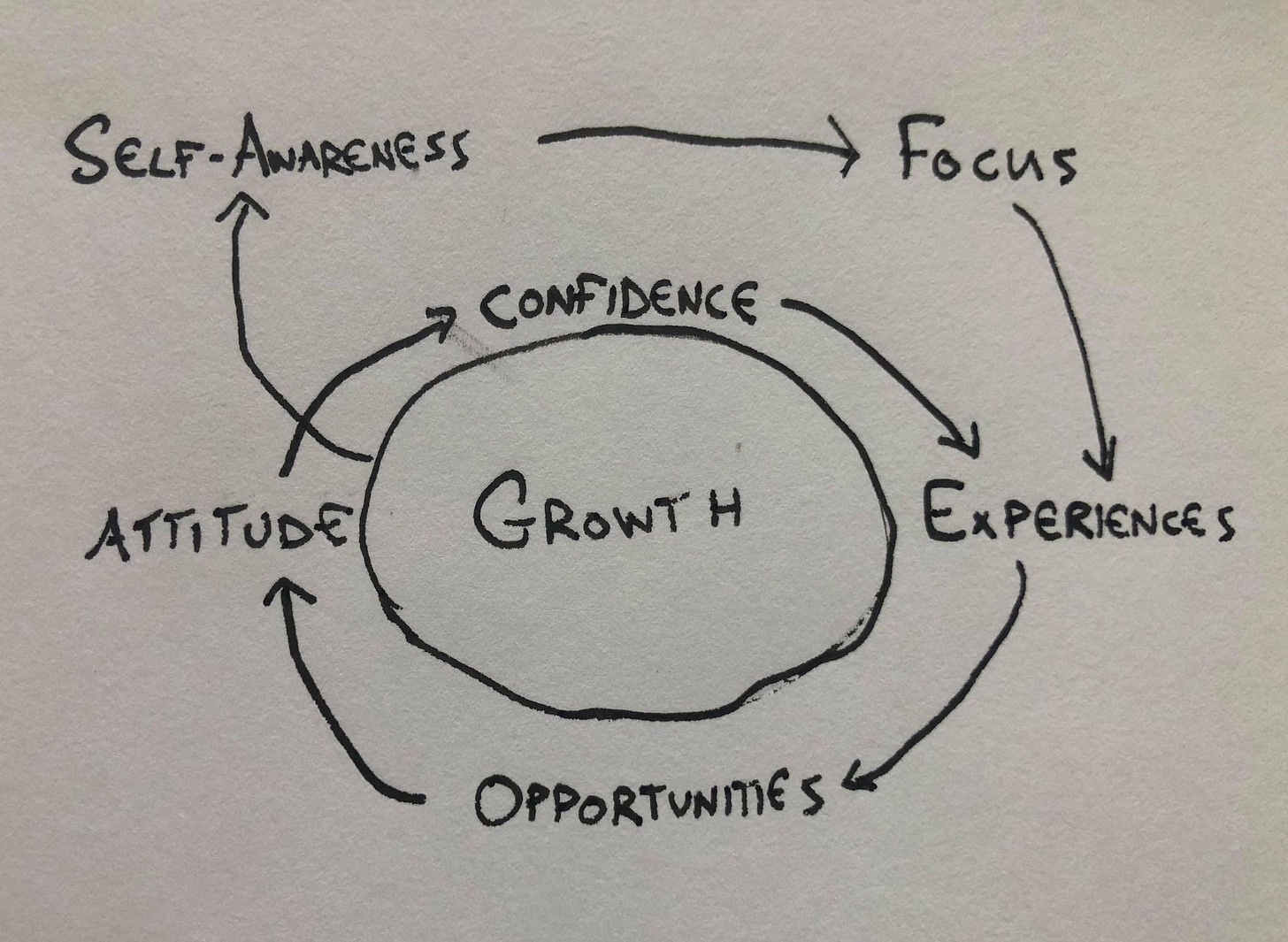

Here’s how I see it:

In a personal growth flywheel, everything starts with self-awareness. Knowing who you are and what you care about is the first step toward developing clarity and focus on what you want. So, as this develops, the understanding helps you seek the experiences you want, which supports the generation of more opportunities. And this brings about a more positive attitude. Then, as your attitude improves, this helps you build better habits, which leads to even better experiences. The flywheel rotates, and slowly but surely, things get better and better, leading you on the path to your greater joy, success, and growth. Sounds pretty good, right?

While many of us have likely experienced some variation of this process, most of the time things don’t really work this way. And for obvious reasons. There is no perfect focus. Self-awareness is a moving target. Experiences aren’t clearly good or bad in the way the model suggests. Attitudes are relative to time and circumstance. Growth rarely feels like a continuous, accelerating process. It tends to happen in spurts—slowly, and then all at once.

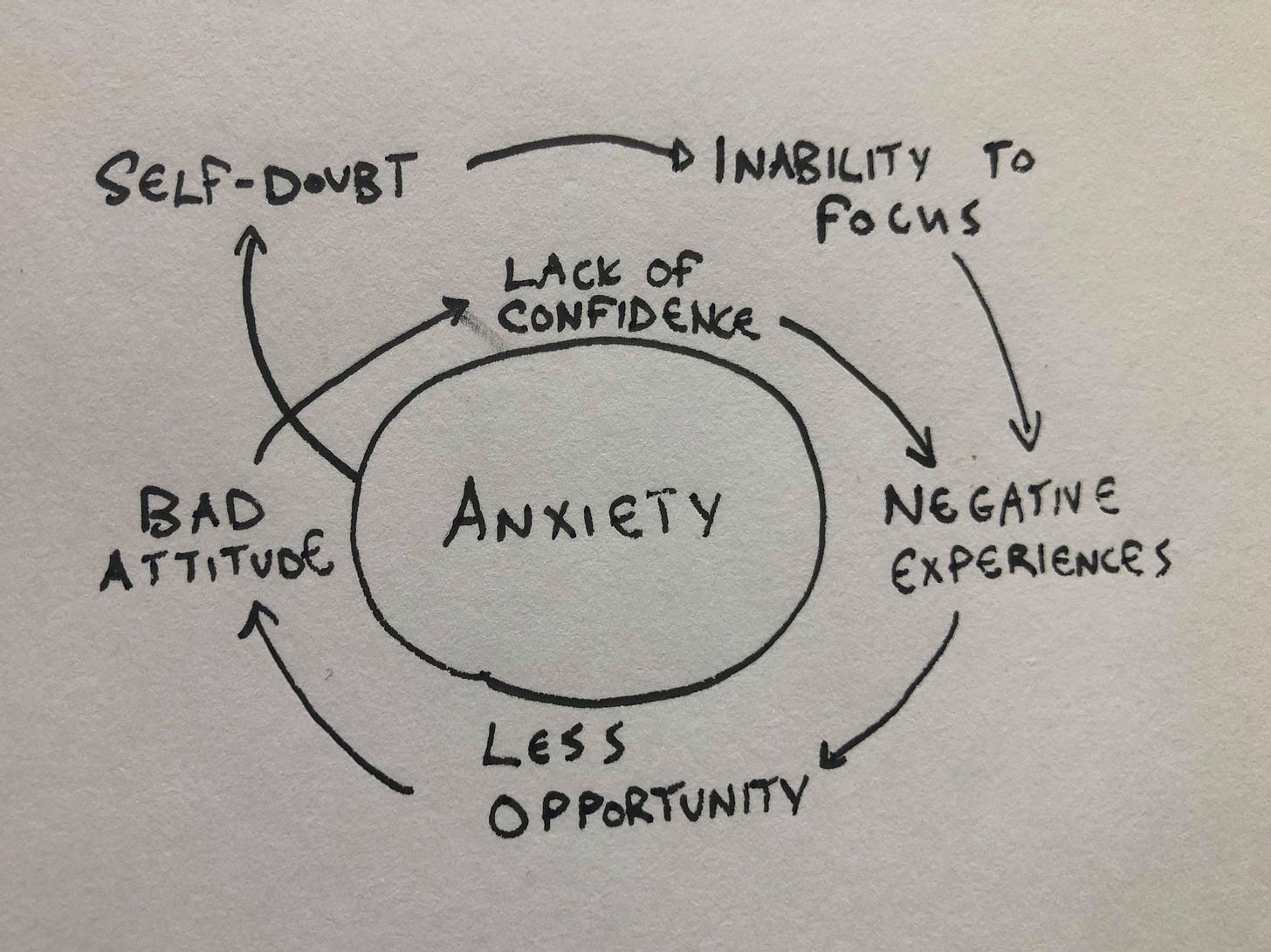

And just as in business as in life, these systems work just as effectively in the opposite direction. Collins calls this regressive pattern the doom loop. When broken inputs are introduced, they not only slow down each of the axes, they can actually cause them to move in the opposite direction. Things that were previously positive become negative.

When things aren’t going well, people react hastily and shift directions. In a struggle to course-correct, they attempt to reconfigure the overall strategy instead of focusing on what’s actually wrong. The result is wasted effort and lost momentum. Instead of accelerating growth, it accelerates losses. Things continue to get worse until something is done to re-frame the system. And the process continues.

This is why emotions like anxiety and depression tend to feel like they’re compounding. We often describe these emotions as cycles that spiral and spin out of control. It feels this way because once these feedback loops begin to spin, they’re difficult to stop. They build because they’re part of a process:

Self-doubt leads to a lack of focus which leads to negative experiences. Once things begin to filter through a lens of negativity or sadness, our attitudes change, our habits shift, and fewer opportunities come our way. And this tends to reinforce the negative operating model. This will usually continue until small steps are taken to reverse the cycle and push the loop in the opposite direction.

In this sense, the analogy that depression feels like drowning is spot on.

Loops on loops on loops

After thinking about this concept for a while, I started to ask myself a perennial question: why do so few people reach their potential? If there’s a natural formula for these things, why is the application of it so difficult? Why does growth happen in stages, and not in a perpetual climb? Why aren’t we all Tony Robbins?

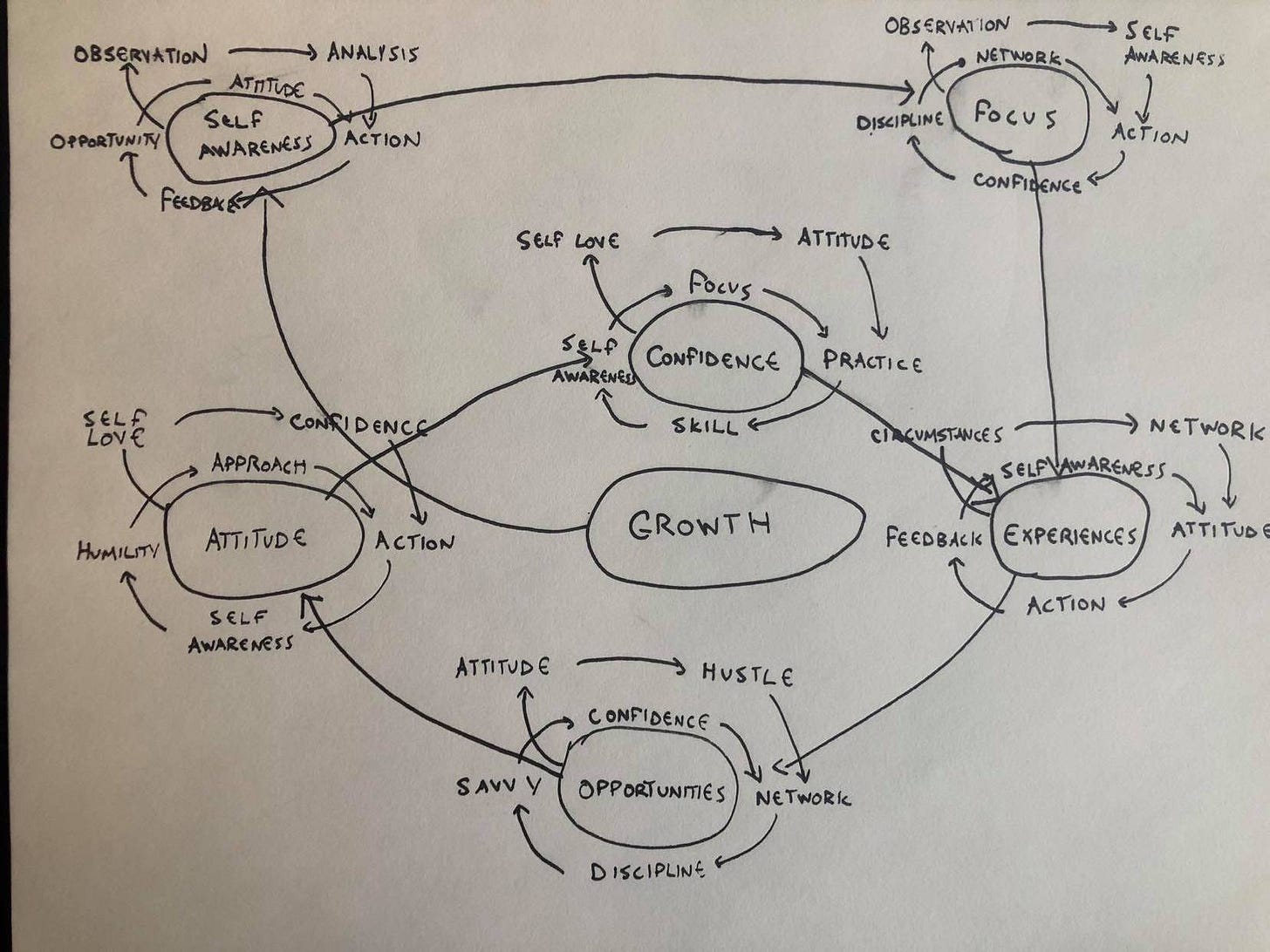

I started to realize that life is a lot less like the chart above, and a lot more like the one below:

Each of these rungs isn’t a static process; each of them is a feedback loop, a complex system with its own intricacies and patterns. Self-awareness is a system that involves observation and feedback, and metaphysics. Focus is a system that demands clarity on values, and attention, and discipline. Confidence is about bridging the gap between expectations and reality. Finding opportunity is about being a good person to work with, and putting yourself out there.

And so the challenge of growth is actually the challenge of coordinating an army of subsystems, all of which begin at different levels of development and require different strategies for improving. The reason that pushing the flywheel takes so much effort is that it’s like being a project manager for an expanding spectrum of processes, many of which overlap and counteract each other.

And it doesn’t stop here. If each of the main axes can have its own sub-system, why can’t the subsystems have subsystems? Taken to the extreme, each of these sub-systems involves their own flywheel regression that proceeds ad infinitum. The analysis rung of the self-awareness sub-wheel requires its own feedback loop. Observation has its own process, too. But for the sake of sanity, let’s stop here.

Is this a useful metaphor for life?

In the flywheel universe, you are the CEO of your life, and success depends on your ability to apply process improvement strategies to everything from self-awareness to value clarification. Great people—in this framework—are the result of systematic mastery. They achieve breakout success through strategy, rigor, and discipline. Life is a continual climb, and it’s improved by working on each ‘muscle group’ individually. Bring them all together and you have growth.

In real life, things aren’t so binary. In the trenches, most things are subtle blends, whose value can only be measured relative to something else. There is no perfect self-awareness, just relative gradations shaped by our values and experiences. There are no perfect experiences; only ones that are right for us to have in that particular moment. But even if it’s not a perfect analogy, I still think there are some important insights that we can take from the model. In particular, there are three that I want to leave you with.

The first is that, in life, we’re so often caught up in the weeds that we don’t think about how the work we do in one area is related to the other parts of our lives. How does improving our relationships lead to greater self-awareness? How does eating healthy allow us to feel more productive? Paying attention to the way wins build off each other is often just as important as focusing on the way we minimize losses. There’s a design imperative in there: learn to create so that one system's fruits can be passed on to others.

The second is the opposite. Improving our lives rarely happens on the level of the big picture, it happens in the incremental improvements we make on a daily basis. Although the big questions are important, the way to improve is by diving into the intricacies of each sub-system and working on what’s within our control. This can get a bit unruly if we focus on the subtleties too much, but thinking about 10% improvements can go a long way over time.

And this is the third point of the model: breakout success isn’t spontaneous—it’s not a product of luck or chance. There is no real overnight success. Success is the process of getting up every day and doing what you can to make things better in a controllable, measurable way. It’s not sexy, and it’s slow. But it works. I think that’s what the flywheel means.

Thanks a lot for your time. If you enjoyed this, please share it with a friend or subscribe.

Life is so beautiful,

Sam

Note: One of the best parts of writing this essay was thinking through each of the sub-components (and the sub-sub-components) of growth. What are the six main parts of confidence? Your theory is as good as mine. But coming up with one was a lot of fun, and forced me to try and define these very complicated terms. If you’re up for the challenge, it might be a fun exercise for you, too.

What’s in your personal growth flywheel?